Piranhas, a small town in the rural backlands of Alagoas, northeastern Brazil, holds in its stones—and in the memories of its people—one of the most violent and symbolic chapters in Brazilian history: the end of the cangaço.

In 1938, at a place called Grota do Angico, near the town of Piranhas, the notorious bandit leader Lampião, his partner Maria Bonita, and most of their group were killed in an ambush. This event marked the final chapter in a saga that had haunted the arid hinterlands of Brazil for more than a decade. Lampião, known as the “King of the Cangaço,” and Maria Bonita, who became an icon in her own right, left behind a complex legacy of violence, resistance, and myth.

The cangaço was a social and cultural phenomenon that emerged in the 19th century and lasted into the early 20th century, mainly in Brazil’s semi-arid northeast region, known as the sertão. At its core, it was a form of social banditry—groups of armed men, called cangaceiros, roamed the countryside, robbing from the rich, occasionally giving to the poor, fighting against oppressive landowners (coronéis), and often blurring the lines between outlaw and folk hero.

The cangaço developed in a time when the Brazilian interior was ruled by a system known as coronelismo, where powerful rural oligarchs—coronéis—held local authority through land ownership, political influence, and private militias. In this context, violence became a common tool for resolving disputes and maintaining control. The cangaceiros were both a symptom of and a reaction to this world: sometimes acting as rebels, sometimes as hired guns for the very elite they opposed.

Some local oligarchs armed and protected cangaceiros when it suited their political interests. There are even claims that at certain points the Brazilian government considered co-opting these outlaws for official purposes, recognizing their influence over vast regions where state presence was virtually nonexistent.

Virgulino Ferreira da Silva, better known as Lampião, is perhaps the most famous cangaceiro in Brazilian history. To some, he was a ruthless criminal who extorted, murdered, and terrorized the population. To others, he was a rebel against social injustice, a man who challenged the entrenched power of the elite, and a symbol of resistance in one of the poorest and most neglected regions of Brazil.

Lampião’s fame was not only due to his violent deeds but also his sense of style—he and his band dressed in elaborate leather outfits decorated with coins, stars, and embroidery, mixing indigenous, military, and cowboy influences. They became visual icons of the cangaço and part of the region’s folklore

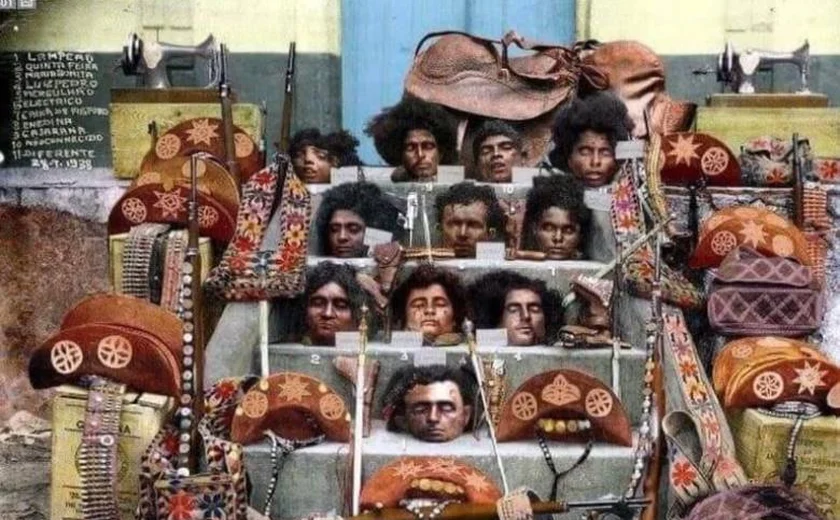

The name “Lampião” was no coincidence: he became famous for his remarkable skill with a rifle, firing so many shots that his weapon would light up the night in the caatinga. His fame spread quickly, and for nearly two decades, Lampião led one of the most feared groups in the sertão, accumulating wealth, power, and, of course, notoriety. His brothers died in the cangaço before him, and on countless occasions, he escaped from death – whether by bullet, knife, poison, or fire. The rumors of his death, which surfaced repeatedly, only fueled the myth of his immortality. That’s why, when he was finally captured and killed, his head – along with those of his men – was displayed publicly as cruel and definitive proof that the “king” of the cangaço had met his end.

In 1931, Lampião met Maria Bonita, who at the time was known as Maria Déia. At 20 years old, trapped in an unhappy marriage, she decided to leave her family behind and follow Lampião and his gang. Unlike many other women who were abducted, researcher Adriana Negreiros, author of the book Maria Bonita: Sex, Violence, and Women in the Cangaço, which paints a harsh picture of the women who accompanied the bands, argues that Maria Bonita joined the gang by choice.

Maria Bonita is often depicted as the first woman to enter the cangaço, but she was not the only one. She became a symbol of defiance for occupying spaces that women had not been allowed to before. However, unlike the romanticized image of the “Queen of Cangaço,” many women were abducted, abused, and forced to follow the bandits. Additionally, Adriana also criticizes the portrayal of Lampião as the “Robin Hood of the Sertão.”

“Some social movements have tried to portray them as revolutionaries, as if they had a political understanding of unequal land distribution—but they didn’t. Lampião wanted to become a coronel (a regional oligarch). He said in interviews: ‘I want to be a ranch owner, a governor.’ He didn’t want to organize an uprising of oppressed peasants. That’s a misconception. Poor people were caught in the crossfire. They were victims of both the cangaceiros and the state police (forças volantes). They had nowhere to run. If someone’s house was visited by bandits and they complied, the police would later retaliate, labeling them as ‘friends of cangaceiros.’ The idea that they handed out money is a myth. Occasionally, Lampião would give gifts—but it was PR. He was a genius at public relations. It was all about earning sympathy in a particular area, so locals would protect him. In films, you see scenes of them entering towns and throwing things into the air. They might have done that—but it was likely just to drop weight from their bodies, not generosity. Lampião had no class consciousness. If he had an ally who was a wealthy landowner and that landowner had a conflict with a small farmer, Lampião would side with the landowner—no question. He wouldn’t say, ‘I’ll defend my fellow poor and oppressed.’ On top of that, he was a racist. He hated Black people.”

According to journalist and author Adriana Negreiros, who wrote Maria Bonita: Sex, Violence and Women in the Cangaço to the BBC News, it’s a mistake to romanticize the cangaço as a revolutionary movement

The brutality of the cangaceiros eventually triggered a harsh response from the Brazilian state. In 1938, Lampião, Maria Bonita, and part of their group were ambushed and killed by the police in a place called Grota do Angico, in the northeastern state of Sergipe. Today, you can visit the so-called Cangaço Route starting from the historic town of Piranhas, in Alagoas. Curiously, the route open to the public doesn’t follow the path the cangaceiros themselves took, but rather the one the police used to track and eliminate them.

In Piranhas, after the ambush, the severed heads of the cangaceiros were placed on the steps of the town hall. Photographs of the scene, disturbing and symbolic, came to represent the brutal end of an era. Yet the legacy of the cangaço, like the arid northeastern backlands known as the sertão, lives on in Brazil’s collective memory. Museums, folk plays, and traditional cordel poetry (a form of illustrated popular literature) continue to preserve and retell the myth of the cangaceiros—figures who still captivate those trying to understand what made them both heroes and villains.

Today, walking through the sun-scorched trails of the sertão where echoes of past battles still seem to linger, it’s hard not to ask: were Lampião and Maria Bonita simply symbols of resistance, or were they also the inevitable result of a system that created and sustained them? And when visiting the Museu do Sertão (Backlands Museum), which immortalizes the end of the cangaço, another question arises: has the myth we’ve built around them blurred the reality of a violent cycle that, for many, seemed to have no end?

Historical Curiosity: By the end of his life, Lampião was physically weakened. He had lost the sight in one eye (“Having two eyes is a luxury,” he used to say) and had a badly injured leg. At the insistence of Maria Bonita, he eventually agreed to have surgery on his ailing eye. To do so, he checked into a hospital, disguised as a wealthy landowner, and stayed there for a month. Upon leaving, he allegedly wrote on the wall: “Doctor, you did not operate on any landowner. The eye you removed was that of Captain Virgulino Ferreira da Silva, Lampião.”