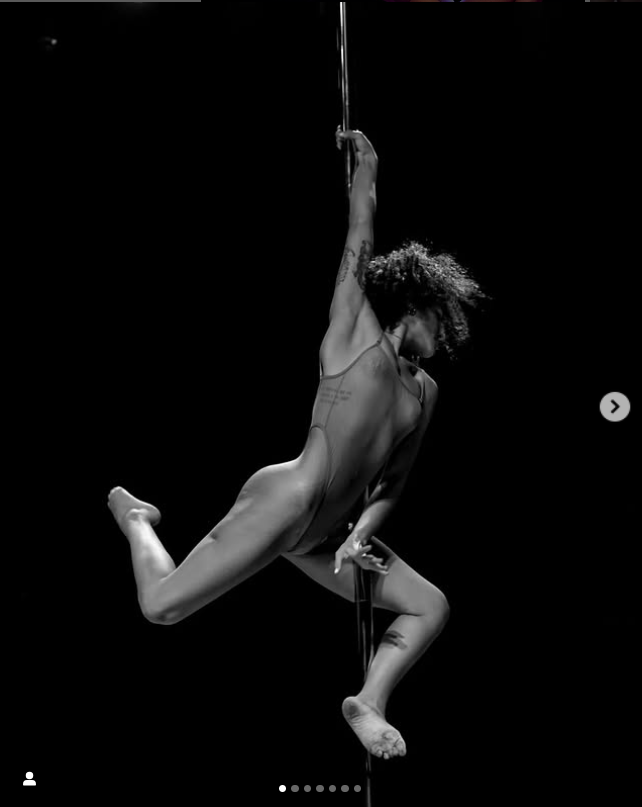

Going against the grain of elitist studios and the expensive logic of empowerment, the Perifa na Pole project transforms dance into a political, inclusive, and vital act for peripheral, Black, trans, and Indigenous bodies.

In a room in Vila Guilherme, near the Galeria do Rock in São Paulo’s north side, pole dance classes rise like totems of resistance. There, the Perifa na Pole project turns pole dancing into a tool for empowerment, especially for Black, Indigenous, trans, and peripheral people. Perifa was born in 2022, when Vitória Grassi and Isabella Kniepert—two women passionate about dance—grew uncomfortable with the inaccessibility of the practice and decided to make it possible for those who had never had a place in it.

Traditionally associated with strip clubs and surrounded by stigma, pole dance is being redefined by collectives like Perifa na Pole.

The classes are free, and the only requirements are commitment, respect, openness, and a present body—even if that body is tired, insecure, or unsure. “Sometimes they’re mothers, sometimes older people. When we become mothers, our bodies change—there’s no denying it. So the project really embraces real bodies and the fact that any body is capable of anything. Any body, you know?” says Isabela. “The instructors there are deeply respectful of each body’s way of expressing itself, its limits, everything. So within our space, that’s always respected. The idea is to create a space where people feel truly comfortable,” adds Vitória.

Between Taboo and Liberation

Mayara Leonel, dancer, actress, model, performer, psychologist, and Perifa student has carried dance in her body since childhood. But for a long time, dancing wasn’t an option. It was a threat. “My father used to say that dancing was for whores, that I’d end up as a cabaret dancer.” A Black woman with wide hips and a big butt, she was often cast into the role of someone who didn’t need to try hard — someone who would get by “with her body.”

“My dad was always very wary of that because he could see the predatory stares from his own friends. He was very protective of me when it came to harassment, and he could feel that energy, you know? That people saw me through a sexual lens. So anything that put me in the spotlight — dance, theater — he preferred to steer me away from.”

May’s dancing started in the streets, in terreiros, in capoeira circles, in axé and hip-hop. “I was always the little girl dancing at family barbecues, the one causing a stir, the one everyone pointed at and said, ‘She’s got talent.’” But that talent remained just an idea. “My mom saw it, but she didn’t know about public programs, and she couldn’t take me to classes.”

As a teen, she secretly taught dance at a community program called Escola da Família. But life took a different turn — early motherhood, an abusive relationship, and slowly, everything she loved was silenced. Dance, theater, art: all pushed aside for a while. Her reconnection came years later, once she had already earned her psychology degree.

“It was studying psychology that made me realize dance was a real need for me. And when that clicked, I enrolled in a performing arts course, completed a technical dance degree, and through ET (Escola Técnica), I found Perifa.”

May signed up for Perifa na Pole for the first time in 2022 — but didn’t have the courage to show up.

“I’m a very insecure person — about myself, about my dancing. My father always said dance wasn’t for me, that dance was for whores. I’ve always had this connection between my body and vulgarity, and dance. My style of dancing is very pelvic. Whenever I dance, my hips naturally take center stage. I kept watching pole dance from afar, and even though I admired it — thought it was the most beautiful thing, super artistic and poetic, plus there’s the athletic side too — I still felt insecure. I didn’t go.”

The same thing happened again in 2023. Another failed attempt. It wasn’t until October last year that she finally went. She sent a message to one of the organizers, explained her previous absence, and was welcomed with open arms. “From then on, I stayed. I fell in love.”

But the experience was more than just technical or aesthetic. It was vital. “Perifa became like a gear for me. As I started moving within the project, other things in my life started moving too.”

In 2023, May lost a daughter. “It was the most devastating moment of my life. I lost a part of my dreams. It felt like a piece of me had been taken, and Perifa gave me the oxygen I was missing. I was walking through a desert, finding nothing — and then suddenly, I could breathe again.”

In that context, the project became a shelter. Soon after joining the classes, May was accepted into the São Paulo School of Dance. She began exploring other dance practices again, teaching, reclaiming her body with freedom. The reframing of pole dance became a personal confrontation too.

“Because I am a vulgar woman. I dance, I shake my hips, and I have no problem with vulgarity. In fact, I think vulgarity is part of who I am. I’m someone who likes to express myself, who has sexual freedom — and I don’t put limits on my own desires.”

Slowly, family judgment gave way to a new mirror

“Pole made me reflect on my own body, on my own prejudices. Even though I’m politically aware, I still had taboos. That whole idea that women who do pole dance are sluts, sex workers, or promiscuous… Well, yes, they can be bold, they can be women who enjoy exploring their libido and their sexuality — because it is pleasurable, and we can’t pretend it’s not. But beyond that, it’s about power, you know? About being a woman who can do things, who can be a pole dancer, who can be multiple. Women, men, people in general — we have this ability to be many things. I can be an excellent psychologist, in my office or in online sessions, and I can also be an excellent pole dancer, and I can give lectures, and I can be an excellent mother. That’s life: we don’t have to fit into one box. We have the ability to explore the world — and our bodies — in so many ways, but because of imposed norms, we end up limiting ourselves and suppressing our desires. I think that’s one of the things pole dance brought me: reflection.”

Audio in Portuguese:

How much does it cost to climb the pole?

Pole dancing is expensive. Very expensive. A single drop-in class can cost over R$ 60. A training outfit can exceed R$ 200. A pair of imported shoes, considered a reference among practitioners, doesn’t go for less than R$ 800. A pole by itself can cost more than R$ 1,500. And that’s not even counting the fees to participate in festivals, events, and competitions — which go over R$ 250 just for registration.

“You keep spending and it almost feels like a pyramid scheme. We want to be validated. I think in any sport we end up seeking recognition, but accessing those spaces is very expensive. For a pole dance festival, the registration fee alone is over R$ 250. It was really expensive to participate. Then there’s… let’s say, on the day of the event, you want to do your hair, you want a nice costume, you want this, you want that…,” says Isabela.

The idea of empowerment sold through pole has been co-opted by a market logic that excludes those who can’t afford the costs. The two agree on one thing: if it were truly about empowerment, the sport would be made accessible. A survey conducted by the founders of Perifa with 129 people reinforces this scenario: among those interviewed, the majority reported a monthly income between R$ 1,000 and R$ 3,000 — while expenses with pole dancing could reach up to R$ 700. Beyond the financial aspect, 100% said they would attend free classes in cultural spaces if that opportunity existed.

INTEREST IN THE SPORT

Over 80% of respondents have either practiced or are interested in practicing pole dance.

MONTHLY INCOME

43% have a monthly income between R$ 1,000 and R$ 3,000.

EXPENSES RELATED TO PRACTICE

50% spend up to R$ 700 per month on pole dance.

ACCESSIBILITY

98% said they would be interested in attending free classes in cultural spaces.

REPRESENTATION

61% reported seeing few Black, Indigenous, trans, or travesti individuals in classes.

“You want to sell empowerment, self-esteem… you grab people’s attention, and that’s why prices skyrocket. And when we did this survey, we heard from people within the pole community who talked about how pole dance truly changes their lives — how they see themselves, how they view their own bodies. And that’s when we realized: you can’t deny access to those who can’t afford to experience this, to try pole dance, to get to know it — especially because it comes from these people: strippers, sex workers, and so on,” says Vitória Grassi, founder of the project.

At the beginning of the project, the two founders had to turn to crowdfunding, raffles, and partnerships to raise money. With the amount raised, they bought four poles and managed to set up their first classes at the Casa de Cultura da Vila Guilherme, known as Casarão. Since then, they’ve fought to keep the project alive with the support of grants and donations — but the money doesn’t always come through. This year, they’re without a grant, but they’re making do with what they have.

Beyond the financial barrier, there’s another one: the environment. “There are spaces where people simply don’t feel comfortable, because they’re exclusionary,” says Vitória. This exclusion is also felt on stage. Getting into festivals depends not only on talent, but also on connections and resources.

Even so, the project persists. And it’s already starting to open new doors. Some students now compete, teach, and occupy spaces that once felt out of reach. The process is slow, but it’s alive — and growing fast. In just three years, Perifa na Pole has already reached nearly 6,000 followers on social media.

At Perifa na Pole, there is no ideal body. There are diverse bodies — bodies arriving tired after work, bodies carrying children, bodies marked by C-section scars or hormonal transitions. Bodies that, more often than not, had never seen themselves dancing. Bodies that were told their whole lives they weren’t “the right type.” And now, with hands on the pole, they discover their power.

The project’s goal isn’t to extract performance, but to create space. To honor each person’s individual rhythm.

In a dance world that often demands hyperflexibility, strict diets, intense training, and thin aesthetics, Perifa offers a different path. One where consistency matters more than contortion.

“In that more elite environment, people go to the gym every day — like, they have access to a perfect routine. They’re people with privilege. They have time to train, to eat well, and all of that. That’s often just not possible for people from the outskirts, who work two jobs, who are on the clock all day, who don’t have time to train or eat properly. Sometimes they’re mothers, sometimes they’re older people too.” — Isabella Kniepert

Students range from 20 to 70 years old. Cis women, trans women, non-binary people, mothers, elders, beginners and advanced. More than just a collective, Perifa na Pole has become a community. There, between one conversation and the next, between training and stumbling, something bigger is born: a sense of belonging.

“We help each other as a community to grow stronger. Not just so the project grows, but so the people grow — as artists, as workers within the pole dance scene.” — Vitória Grassi

Going against the grain of the industry, the project follows its own rhythm: it offers free training, hosts discussion circles, and receives donated poles so students can practice at home. Some former students are now instructors. Others compete in festivals. The cycle feeds itself — and expands.

As May Leonel said: “I can be an excellent psychologist in my office, and I can also be excellent at pole dance. I can give lectures, I can be an amazing mother. That’s life: we don’t have to limit ourselves to just one role.”

And maybe that’s exactly what Perifa na Pole teaches: that the body is not a barrier, it’s a tool. That dance is not a privilege, it’s a right. And that somewhere between technique and falling, between spinning and dizziness, something greater takes shape — the chance to finally claim your place.