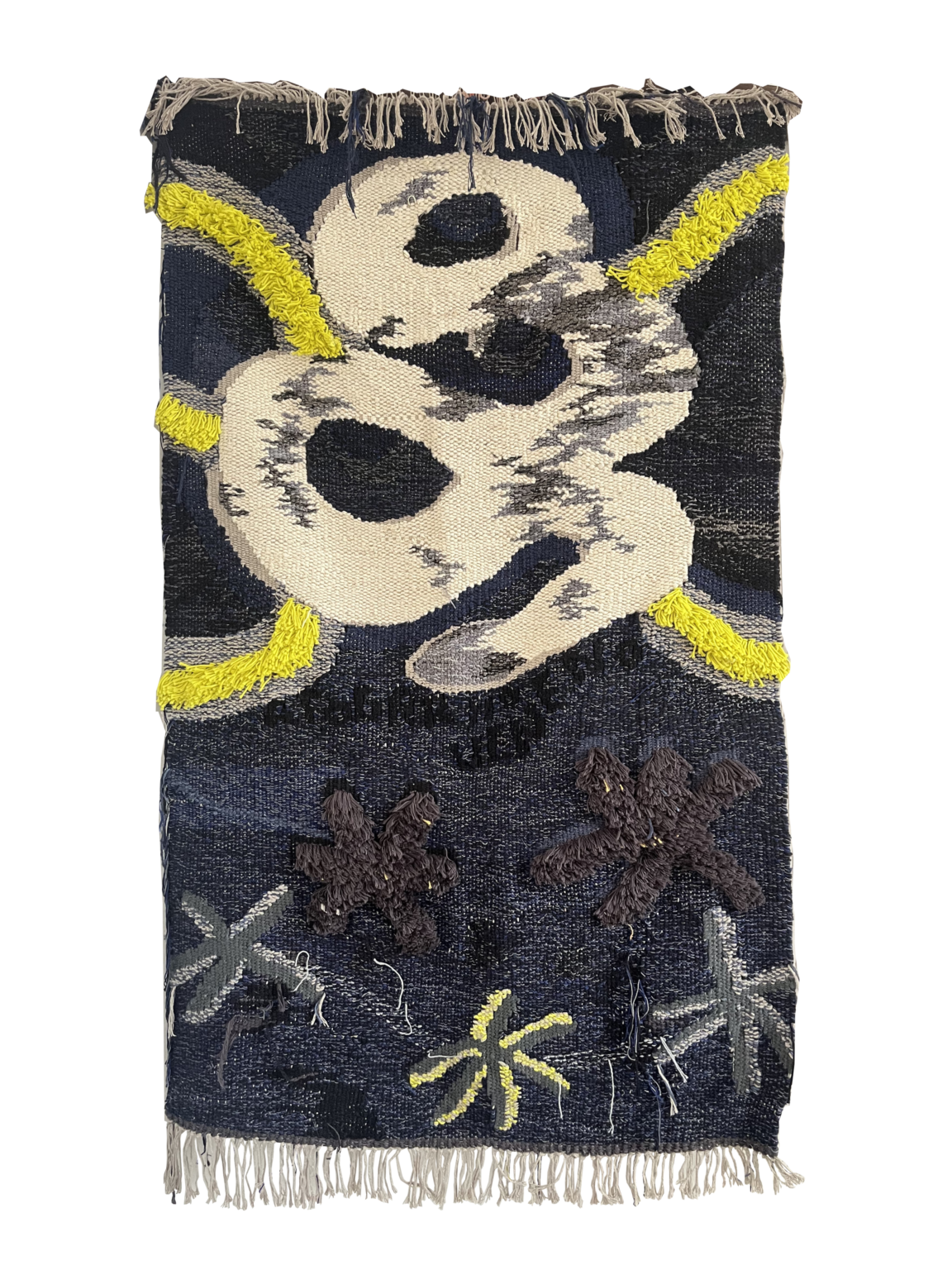

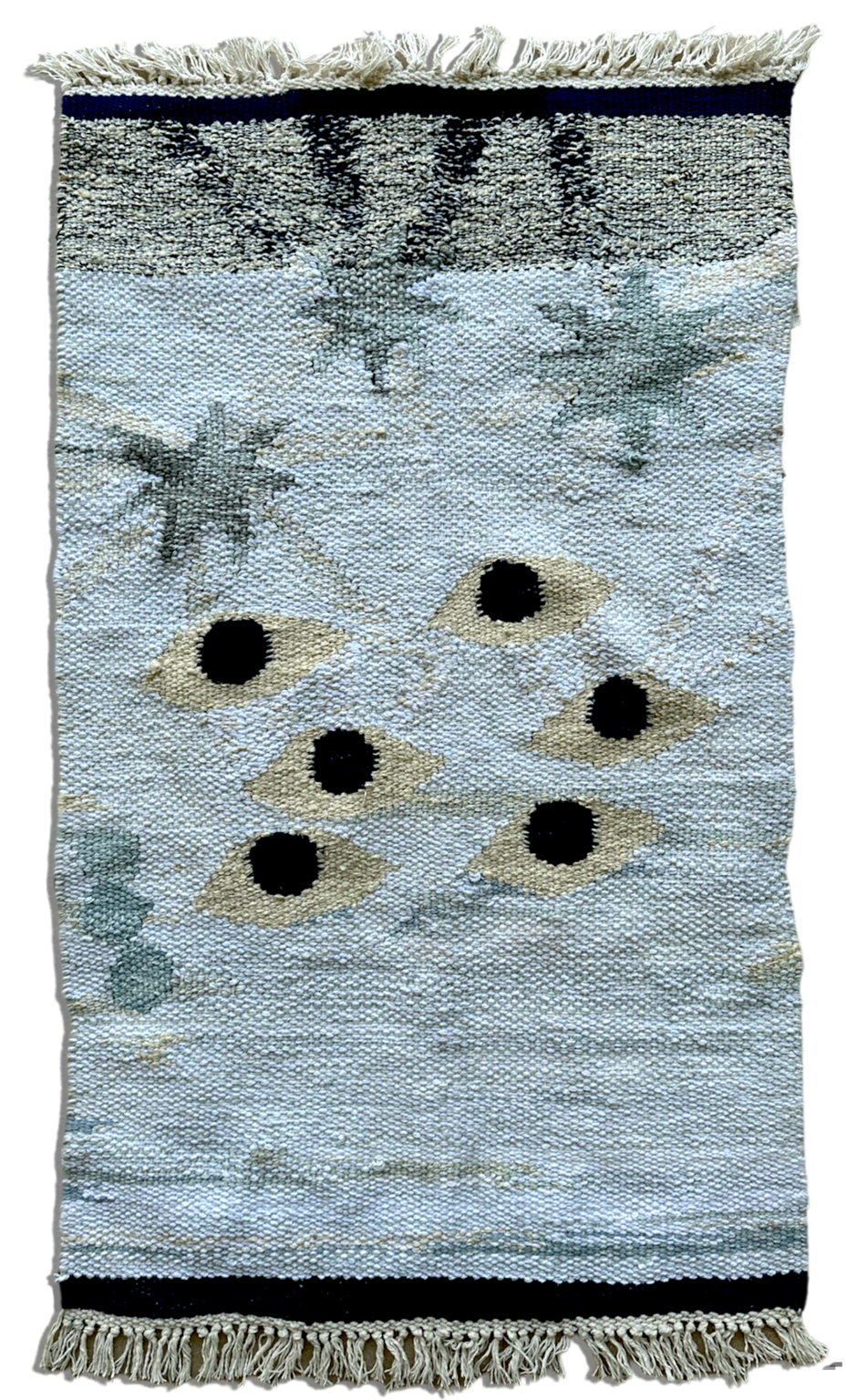

Sophia Zorzi, was born in Minas Gerais, Brazil, where she grew up surrounded by the remnants of the Atlantic Forest—an environment that seems to radiate ancient stories and forgotten mythologies. An artist and weaver, she intertwines these legacies with her own narratives, creating tapestries that go far beyond simple craftwork. Her pieces are sensory maps that explore the intersection between the feminine, the human psyche, and the stars — a mosaic of culture, memory, and spirituality.

Graduated in Fashion Design from UFMG, a member of the Aranha Arranha collective, and participant in programs such as Women@Dior and the Alice Brown Scholarship, Sophia constructs a hybrid imagination that flows between art, craftsmanship, and spirituality, reflecting on time, memory, and belonging.

Among threads and yarns that seem to draw constellations, Sophia speaks with a calm sense of purpose about her search for something deeper, something almost intuitive. “I’ve always been drawn to working with my hands — I used to draw a lot. I loved materializing my ideas manually, you know? So drawing, even the lines themselves, have always been very important to me,” she says.

It was during her time in fashion school, through friendships and unexpected experiences that emerged during the pandemic, that she found herself immersed in the possibilities of tapestry. More than an ancient technique, she discovered in it a form of expression that not only reflected but also shaped her personal research. Over time, the ancestral practice became a language of its own.

“This research and creative process comes to life when it brings together all these spheres: art, fashion, and design. Over time, it started to take shape, and I now find myself somewhere in between these fields — visual arts, design, and fashion alike.”

MashUp: How did your interest in tapestry begin?

Sophia: When I started studying Fashion, I already had a strong interest in textile artifacts. From a young age, I was drawn to embroidery, appliqués, and prints. These techniques always attracted me, but tapestry was something I didn’t really know beyond what we typically see in mainstream spaces. In college, that’s when everything started. A friend of mine, João Marcos Lisboa, was working on his final project, which was a tapestry full of colorful threads dyed with natural pigments, and he taught me several techniques. Later, it became something I started exploring on my own. I learned many things that way, and I think that’s also reflected in my practice—how I think and develop a project. It was important to get in touch with the concept of the warp, the thread that runs vertically, and the weft, the thread that runs horizontally, interlacing everything. That helped me understand how the process works and taught me how to weave on a loom. This material, this knowledge, was fundamental for me. But tapestry itself is something very intuitive. When I started, I wanted to explore every stitch possible. Today, I work with the same stitches, because they effectively achieve the image I want to create.

MashUp: You use a lot of blue in your work. I don’t know if it’s just my perception, but this color seems to be a signature in your practice. Does blue have a special meaning for you?

Sophia: Almost all of my works have at least a bit of blue. It’s probably the color I have the most variations of. I think I like the vastness it conveys, from both the sky and the sea. It feels like a color you can sink into, you know? I want to communicate a bit of that sensation that blue brings me.

MashUp: What kinds of symbolism do you incorporate into your art, into your tapestries?

Sophia: Ever since I was very young, I’ve been interested in mythology. I remember I had books about myths, and it was also during the pandemic, when I was developing my first personal project, that I started diving deeper into that world. I was reading Masks of Fire by Eduardo Galeano, and that inspired me to work with masks. They have this intriguing quality: they’re wearable objects, but at the same time mysterious. I kept thinking about this in-between space—between revealing who you really are or hiding it. So the mask has all that mystery. Because of that reading, these myths started entering my work, but not in a literal way. I didn’t want to illustrate the stories directly, you know?

I’m also very drawn to ancient Mediterranean mythology, and my goal isn’t to illustrate specific scenes, for example. That’s not what I’m after. I like to think more about the feeling a myth evokes. It’s a way of reflecting on universal human emotions—like fragmentation, stubbornness. Feelings that are hard to represent in a concrete form, but that, through tapestry, can become something more fluid, more open. So it’s almost as if I read the myth and let it transform into whatever I feel while reading it. It becomes a kind of translation of my body and my emotions.

MashUp: So you make a kind of association, right? Something more personal with what the myth stirs up in you…

Sophia: Yes, I usually make those associations. There are parts of a myth that remind me of specific moments in my life, like when I felt really strong or, on the contrary, when I felt vulnerable. I like working with those emotional states—bringing closer what is human, what belongs to a body that feels, that moves, that wrestles with things. That’s also the role of myth, right? It’s not just a story, but a representation of our collective memory as a civilization. So when I appropriate the myth, it becomes individual to me, because it’s how I feel it—but it also goes beyond my body, my time. It’s much older than I am.

Maps are another recurring symbol in Sophia Zorzi’s research, connecting mythology, cartography, and constellations. When asked about a mythological figure that catches her attention, she mentions the Hydra. “It guides like all relationships, it guides humanity on Earth,” she explains. “And it’s an inexhaustible figure. In the myth of Hercules, every time he cuts off one of the Hydra’s heads, two grow in its place. This relates a lot to my creative process: every time I create something, I feel the urge to create more. Each work opens up new possibilities, expands my repertoire.”

But the fascination with the Hydra is not only symbolic: “The heroes in these myths always face monsters, many of which are feminine figures. This wasn’t so evident to me at first, but then I realized that these entities that are fought — like Medusa, for example — are representations of the feminine. It’s a way for patriarchy to assert itself, turning women into threats to the hero’s journey.”

—

MashUp: How do you deal with the time involved in tapestry in such a fast-paced world?

Sophia: The time of tapestry is slow. Sometimes a piece can take more than a month to complete. And I watch what was just thread transform, you know? The threads interweave, becoming a rug, a body that has shape, dimension, weight. In a way, it’s like I’m recording time right there. It’s a challenge, really, because in today’s world, we’re pressured to produce at a 2.0 speed, right? But at the same time, there are many things that we simply can’t perceive at that pace. Like matter, for example. What’s fleeting, digital, visual… but it’s not matter, it’s not a physical object. And seeing all of that transform into a concrete object, actually, is something that connects me.

MashUp: Do you sketch these designs beforehand, or do you create as the tapestry takes shape?

Sophia: Each tapestry has a process that teaches me a lot in this sense. Before, I used to choose a protagonist, a form, and start working on it. Then, I would make drawings to try to understand what the piece was asking of me. I’ve always found it very important to “listen” to the work. This is a constant exercise for me, between what I thought the piece was going to be and what it actually becomes. Nowadays, I’ve learned to embrace this transformation more. Before, I would unravel a lot — oh, I didn’t like that color, and I’d undo everything, which made the process even slower. The search for perfection made me want to start over all the time, but tapestry, unlike painting, grows vertically. The process is more gradual, and what seemed like the “mistake” often becomes part of the project. At first, I had difficulty with that.

I started using digital images to help me better understand what I wanted. I’d take old images, which are in the public domain, and edit them in Photoshop. This gave me direction. In the project I’m working on now, for example, I had an initial idea, but when I started working on it, I realized it wasn’t what I wanted. So, this helped me understand how the piece could transform, while still being guided by my references. The digital technique is completely different from the manual technique, and it requires constant adaptation.

When I painted, I had a little more difficulty in this sense, because painting always involves adding one more layer. But in tapestry, the work grows vertically. There comes a point where you can apply embroidery or continue filling it in. In general, I think a lot about composition — it’s one of the most important things in creating an image. The balance of the piece adjusts, sometimes even undoing part of the bottom to adapt everything into the right place. I think that, because it’s a vertical technique, you fill it in little by little, and that makes it easier to understand the beginning, middle, and end of the work.

MashUp: How did your scholarship experiences go?

Sophia: Both were virtual. It was right during the pandemic. I was a scholarship recipient from an international community, and I had the opportunity to present my work there. It was a really great experience because their welcome was amazing, both in the preparation for the presentation and on the day of the presentation itself. It was wonderful to see how these practices happen around the world. Each place has its own characteristics, like the types of weaving (“tear”, in Portuguese), which refer to specific groups or methods, you know? For example, we have the “Mineiro tear,” the “vertical tear,” the “Mapuche tear,” the “French tear”… There’s a lot of diversity. But at its core, the weaving technique, tecelagem, has a common base among these places. It was really great to see how people engaged in these practices welcomed me in this sense.

The other scholarship was part of a program in partnership with UFMG and Women@Dior in partnership with UNESCO. It was dedicated to autonomy, creativity, and sustainability for women in higher education. It was very cool, a high-level program. I was invited to participate virtually, which was really interesting. In the virtual format, you feel a bit of distance, right? But even so, it was an enriching experience.

MashUp: Is there greater visibility for weaving, especially in the south of Brazil? Or do you feel there are more opportunities abroad?

Sophia: I think that, especially in Brazil, there are some contests and initiatives, particularly in the south, that have more established visibility. But compared to what I see abroad, I believe there are more artist residencies and programs geared towards my field outside of Brazil. The art market abroad offers more opportunities for artists who work with weaving and other manual practices.

MashUp: What is it like being an artist in Brazil today? And how do independent artists manage to survive and engage with the art community?

Sophia: Being an artist in Brazil is challenging, no doubt. There aren’t many resources, and the support structure is limited. But I know people who do very well in this challenge, creating their own strategies. I, for example, have positioned myself in three different sectors — besides weaving, I’ve worked with costume design, sewing, and other things. We create strategies and adapt to the circumstances. I think to be an artist in Brazil, you need a good strategy and a clear goal. Sometimes you need to adapt and try to make things happen within what is possible. It’s a rollercoaster. I don’t want to fall into the romanticism of thinking everything is perfect, but at the same time, it’s a choice of field, right?

If you could collaborate with any artist: I would like to collaborate more with the artists around me, with the people who are close. I’m in a moment of really thinking about how my works can connect with others, so I would be very happy to collaborate with my friends, like Abraão Veloso, who also works in tapestry, João Marcos Lisboa, and Luiza Poeiras. I think these closer collaborations have something special, an exchange that is very rich. Also, there are some artists you end up getting to know virtually, through Instagram, and I would love to work with them as well. One example is Marie-Claire Messouma, who has an incredible body of work. She makes tapestries, ceramics, embroidery… it’s very textile-based work, which fascinates me. I really believe that these closer creative exchanges have immense value, and I’m very focused on that at this point in my journey.

The strangest advice you’ve received: I think the strangest advice I’ve ever received was the idea that I needed to have a talent, a gift, or always be inspired to create. That seemed like a setback to me, an idea that can really harm any artist. When a creation doesn’t turn out the way I imagined, simply, and doesn’t reach the result I expected, that teaches me something. It teaches me to keep going, to find ways to improve and develop, and not to give up. I don’t think talent is something innate or something that needs to be waited for. For me, talent is something that develops, that comes with time and practice. Of course, some people have a natural predisposition for certain things, a skill or greater patience for particular activities, but that’s not fixed. I see talent more as a skill that gets honed, a connection you create over time.