In the 1920s, Mexico was a country rebuilding itself. After decades of dictatorship and a bloody revolution, the new government aimed to reinvent the nation — and found a powerful ally in art.

This gave rise to Mexican Muralism: a political and artistic movement that turned public walls into manifestos and artists into chroniclers of the people. Walls became spaces of resistance, identity, and memory not just places to hang paint.

Between 1910 and 1920, the Mexican Revolution challenged the regime of Porfirio Díaz, who had ruled since 1876. Leaders like Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa fought for social justice, land reform, and a government by the people. After the war, the country’s intellectual elite saw an opportunity to build a new cultural identity one that embraced Indigenous roots and brought education to the masses. Art had to leave the museums and enter public life.

In the 1920s, the state began commissioning murals in schools, public buildings, and universities. Even more revolutionary: artists were given full creative freedom. The mission? Democratize art and spread the ideals of the revolution.

Three legendary artists defined Mexican Muralism, each with their own vision of the country’s soul:

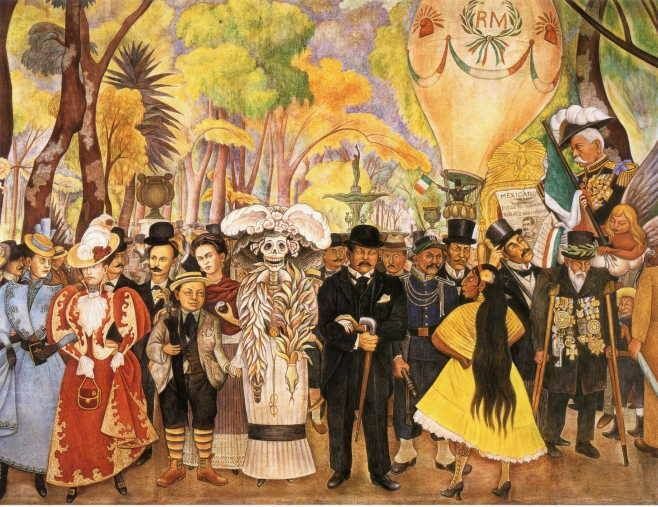

Diego Rivera was the idealist. He lived in Europe during the revolution, and his work reflected a utopian view of the people. Inspired by Cubism and the Italian Renaissance, he used earthy tones, Indigenous symbols, and monumental figures to portray a modern Mexico rising from its roots. A defining moment: Rivera was hired to paint a mural at Rockefeller Center in New York. He included Lenin’s face in the composition. The Rockefellers demanded its removal. Rivera refused. The mural was destroyed. Years later, he recreated it in the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City.

José Clemente Orozco, in contrast, had fought in the Revolution. His work is more somber, critical, and emotionally raw. He distorted human figures, emphasized suffering, and challenged the glorification of war. To Orozco, the Revolution was trauma not triumph.

David Alfaro Siqueiros was the most radical. A young communist and technical innovator, he used spray guns, industrial enamels, and mechanical tools to paint murals full of movement and modernity. His goal? A socialist, scientific future and a new Latin American man.

Women muralists were there, too though often overlooked in the history books.

Aurora Reyes Flores is recognized as the first female Mexican muralist, with works in schools and union halls.

Rina Lazo, Diego Rivera’s assistant for over a decade, blended Mayan cosmology with political critique in her murals.

Fanny Rabel, a Polish-born artist who settled in Mexico, was a feminist, activist, and muralist who believed art could reshape education and culture.

Mural painting wasn’t new in Mexico. Civilizations like the Olmecs, Mayans, and Aztecs created sacred murals long before the Spanish arrived. What changed in the 20th century was the message: Mexican Muralism fused ancestral techniques with modern political ideas like Marxism, utopia, anti-imperialism.

Before Rivera, 19th-century artist Juan Cordero had already explored political murals. In 1922, Rivera painted his first government-commissioned mural, La Creación, at the National Preparatory School, a blend of Christian and Indigenous symbolism.

Mexican Muralism’s influence crossed borders. It inspired Latin American artists like Cândido Portinari in Brazil and Antonio Berni in Argentina. Even in the U.S., it left its mark: Jackson Pollock was briefly a student of Siqueiros. But more than a visual style, the movement spread an idea: art should be public, political, and accessible to everyone.